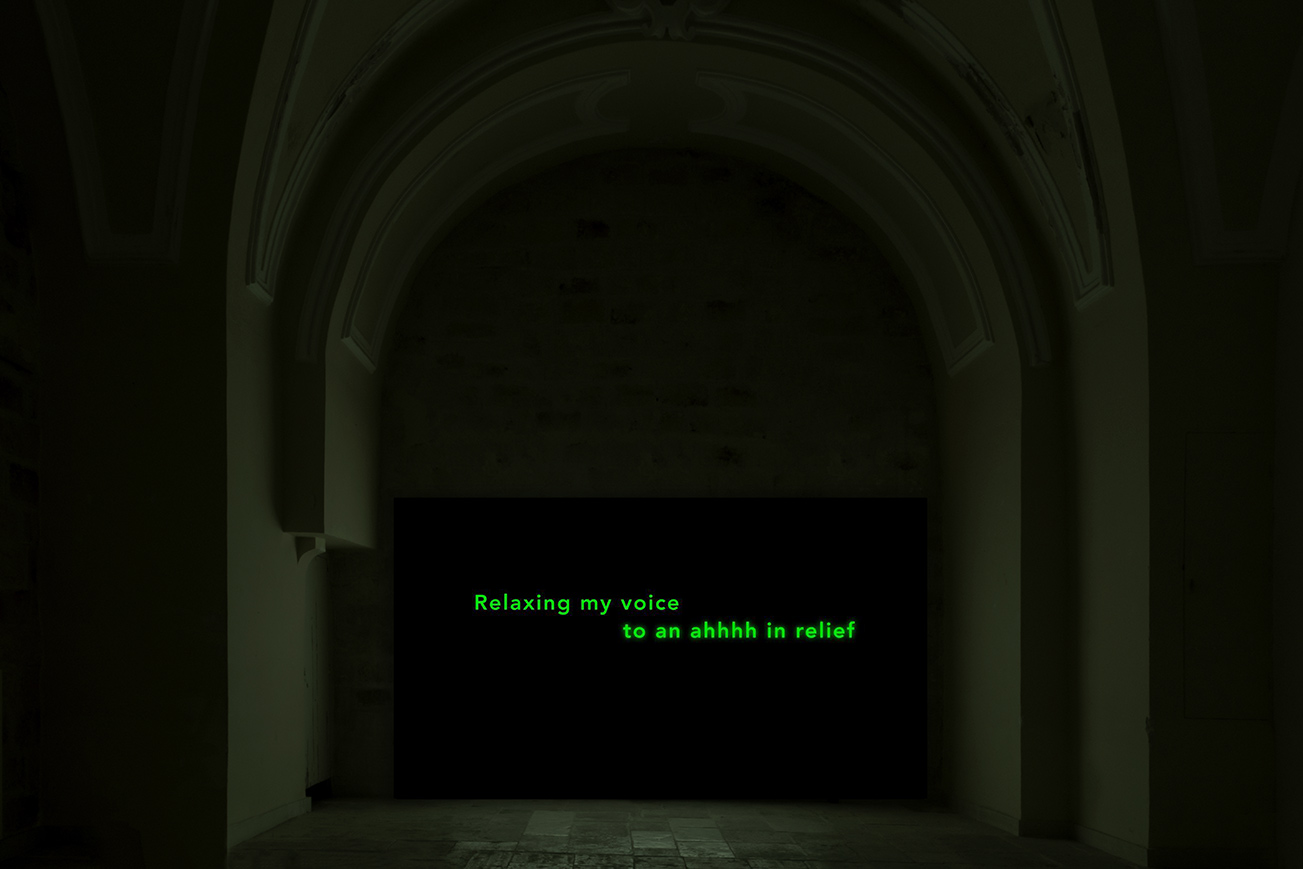

Body snatchers (The Church)

Ed Atkins, Petra Cortright, Julie Grosche, Oliver Laric, Heather Phillipson, Laure Prouvost, Bárbara Wagner & Benjamin de Burca, Jala Wahid

Curated by Like A Little Disaster and PANE Project

12 April / 20 June 2021 @Church of San Giuseppe, Polignano a Mare, Italy

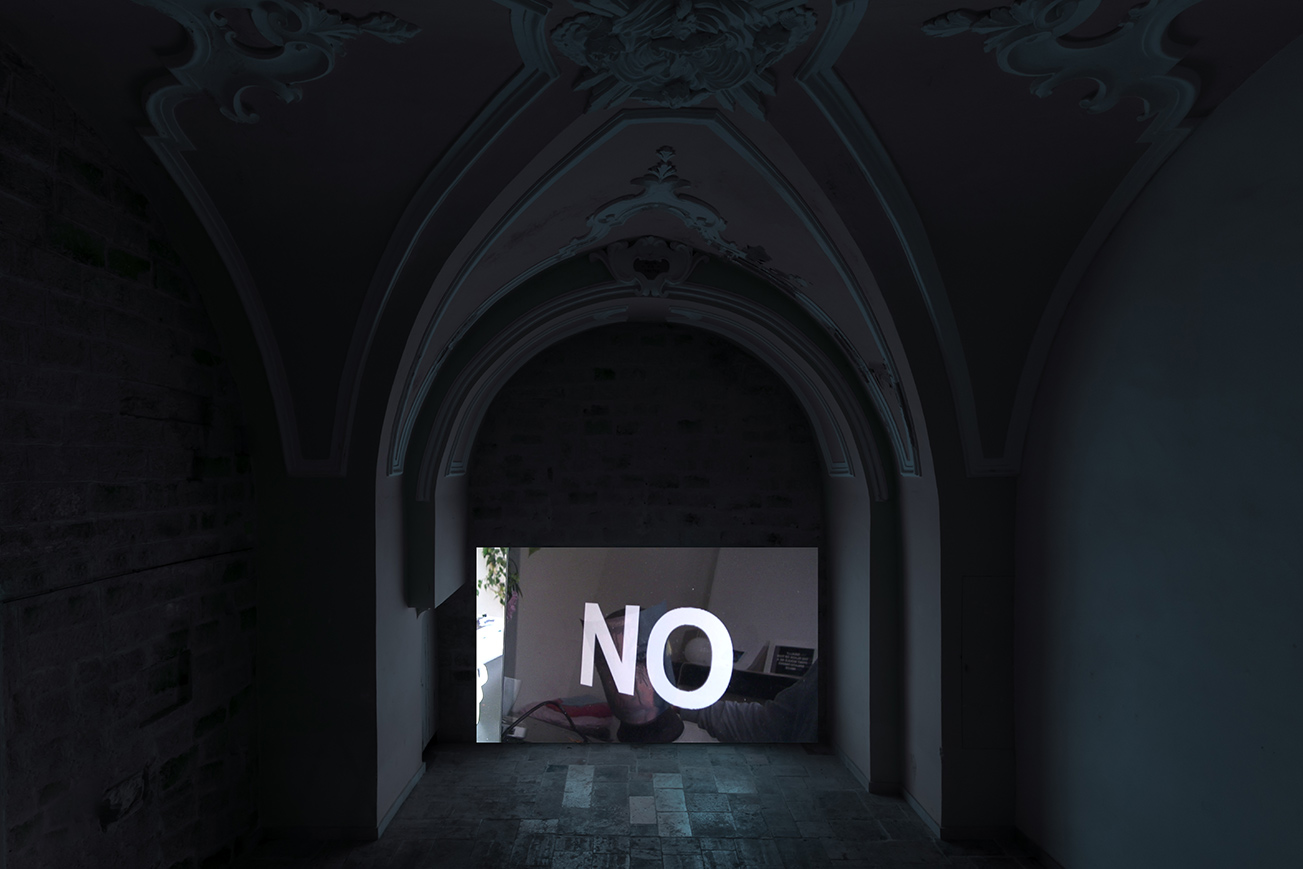

Like A Little Disaster and PANE project are honoured to present Body Snatchers (The Church), a new chapter of the investigation around the languages of international video art in the venue of the seventeenth-century Church of San Giuseppe in Polignano a Mare.

Access to the church shall be allowed to only one person at a time. The exhibition will be experienced only in total isolation. The church will have no staff and no physical interaction shall be allowed. The exhibition experience is thus transformed: from a social and mundane event to a private dimension in which the vision becomes the space of self-reflection.

The projection of each video shall follow a random playlist following the order of the Canonical Hours of the Catholic Church; the hours dedicated to communal and collective prayer.

Liturgy of the Hours

Matins (before dawn)

Lauds (at dawn)

Prime (at 6 am)

Terce (at 9 am)

Sext (at noon)

Nones (at 3 pm)

Vespers (at sunset)

Compline (before bedtime)

—

This bower was my temple,

the fastened door my shrine,

and here I would lie outstretched

on the mossy ground,

thinking strange thoughts

and dreaming strange dreams.

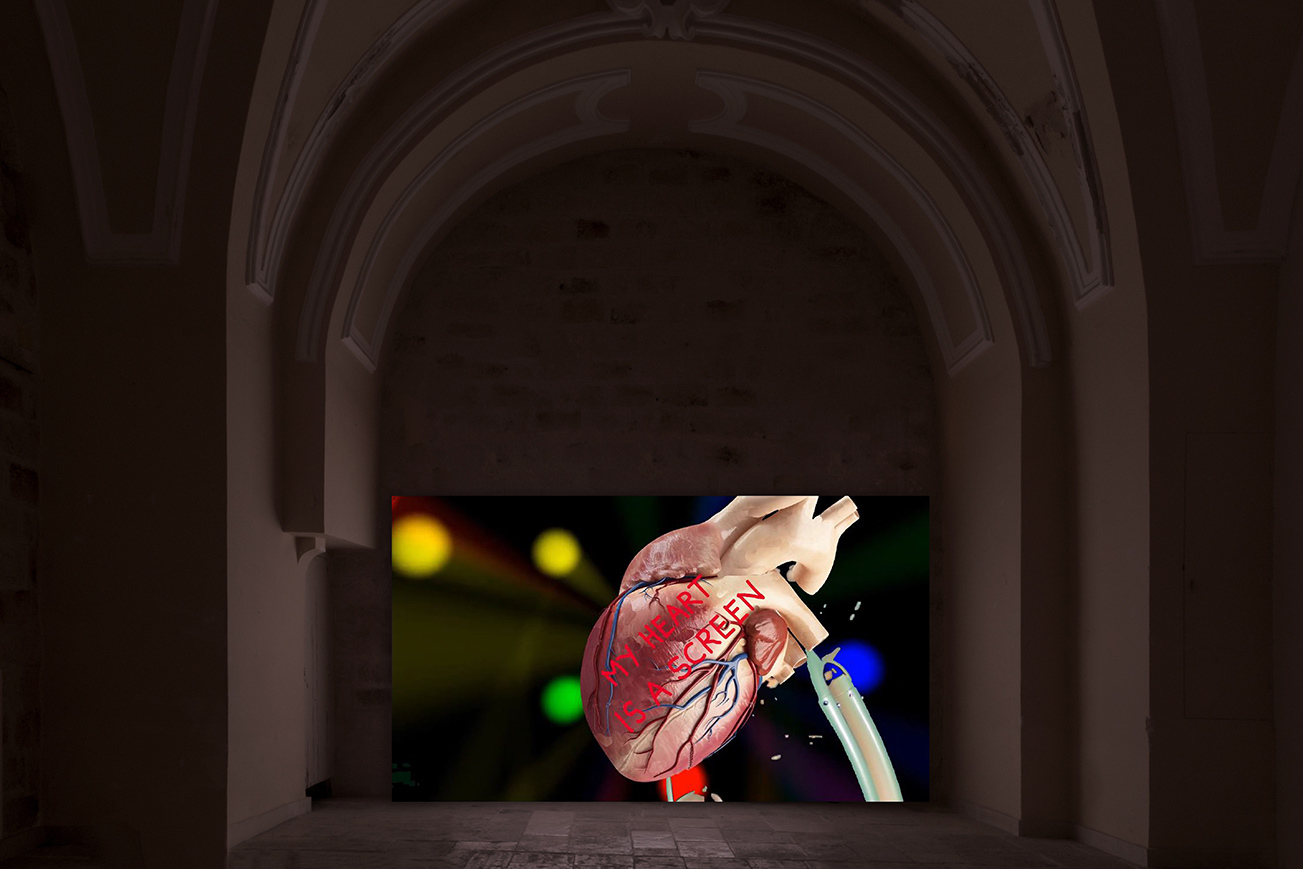

The videos appear as visions, as frescoes that come to life on the walls of the church, as candles lit for a saint or as prayers. The projections work as large mirrors through which the visitor can compare and reflect himself (as a comparison, in the absence of any other human presence).

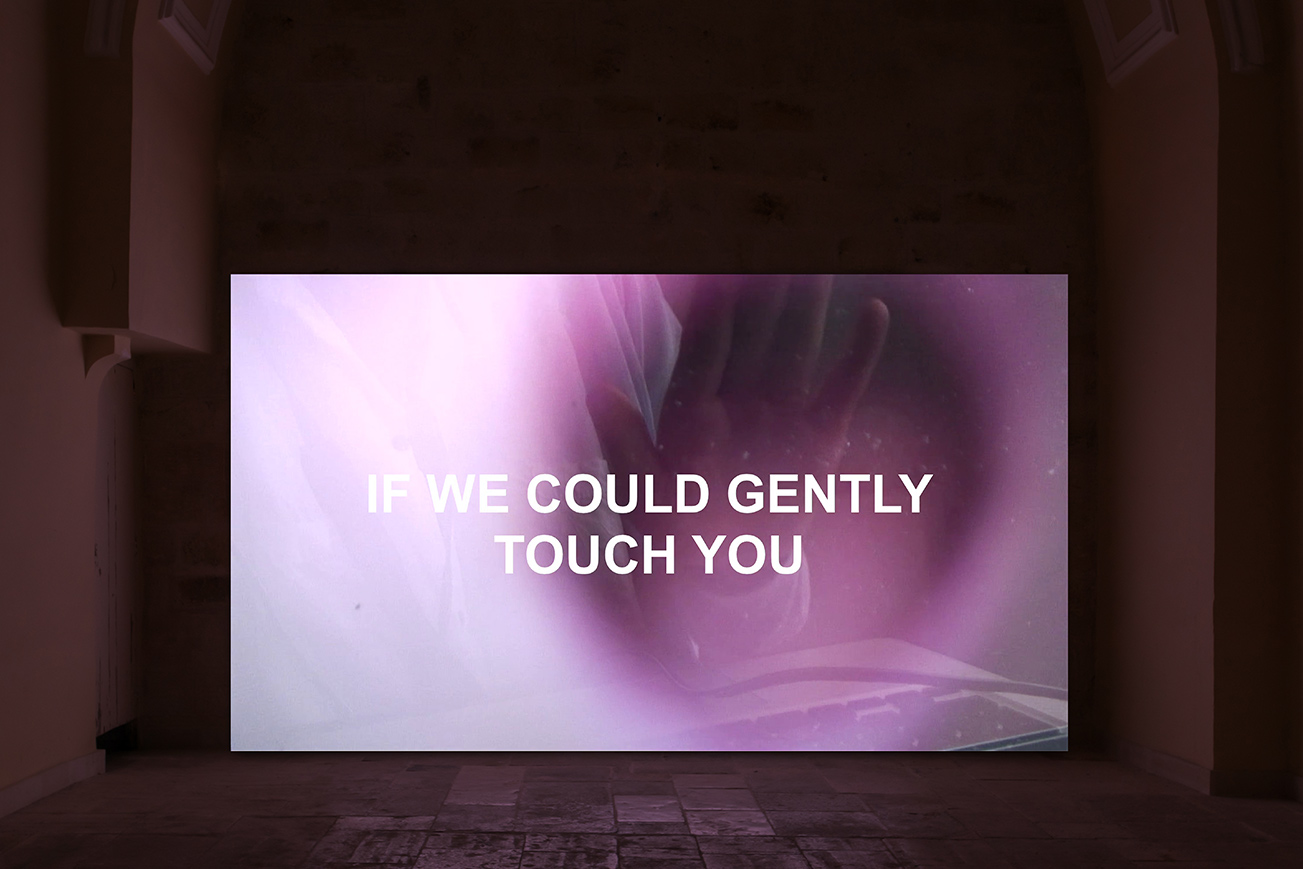

Body Snatchers (The Church) takes place at a time when the rules of isolation and physical distancing are in force, a radically self-reflective time in which the body does not necessarily have to perform or materially manifest itself to others – if not through or within an immaterial dimension. The project becomes extra meaningful given the current situation of social distancing and expansive digital communication. As the longing for physical contact with all that’s left behind, excluded from our intimate bubble, is growing, the confrontation with flat images gets more painful.

We just have to caress the screen and accept the value of the non-material being.

The project is set within a space intended to host the liturgical assembly, an aisle which commonly hosts people who believe in the real existence of the body and blood of Christ, but which now hosts a body forced to believe that the others, their substance, and their physical presence still actually exist. The church is also the place where the faithful believe that the body (the incarnation of the Divine) is resurrected and returned to life after death; a place of life and death, of passage between the two, and of their mutual interchange.

In the Gospels, the empty tomb and the resurrection are one and the same. Women and apostles never see the resurrection as the reanimation of the dead body. They only see the absence of the body and the apparitions in a new and mysterious form, open to interpretations. It is the absence, the emptiness, the substance of resurrection.

The dreamy, awaited, escaped and untouchable body becomes the image of a reproduction which meets the needs of desire. The lost body is really absent, loneliness becomes the place of its abstract presence. So is abstraction itself nothing but absence and pain or is it painful absence?

Waiting for others activates the manipulation of the object of desire, giving it a body, a face, a character, intentions, words, which almost never correspond to reality. The object one waits for itself, the mass-centre of this dynamic, can actually turn out to be nothing more than an imagined object: what is this body if not the product of imagination? Isn’t it an unreal, evanescent body you are actually waiting for? Is the awaited body endowed with its own objectivity or is its image linked, by its very nature, to the subjectivity of those who think it?

In a place whose very name indicates the space dedicated to the community, the gatherings of the faithful and the liturgical assembly, Body snatchers (The Church) speculates on the dimension of isolation, transformation, presence/absence and on passing and crossing physical boundaries, as well as on the concepts of nostalgia, loneliness, pain and grief.